Stephen van Dulken writes:

For some reason quite a number of woman patent holders were involved in spiritualism. One such is Judith Blanche Dwyer. I came across her with her British patent 1899/15879 https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/originalDocument?CC=GB&NR=189915879A&KC=A&FT=D&ND=3&date=18991014&DB=EPODOC&locale=en_EP

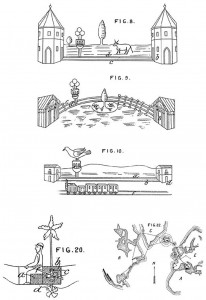

[and show drawing, which is is at] https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/biblio?CC=GB&NR=189915879A&KC=A&FT=D&ND=3&date=18991014&DB=EPODOC&locale=en_EP

She said that she was of 917, Market Street, San Francisco, medium. British patents, unlike American patents at the time, normally gave a full address and often an occupation. The invention is for a bottle which, once emptied, cannot be stopped up again. It was to prevent unhygienic reuse of bottles by unscrupulous merchants. It was a common subject among inventors in late Victorian times, including by women. I thirsted to know more about this woman. To me the invention is only half the story. As I normally do, I checked for “equivalents” – the same invention published in other patent systems. Besides showing their business strategy, this can give extra information. American patents at the time, for example, usually cited the citizenship of the inventor – very helpful in a cosmopolitan city such as San Francisco.

I first looked on Google and found, on a shipping site http://www.immigrantships.net/v4/1800v4/mariposa18941122.html ,a list of “alien immigrants” on the SS Mariposa, sailing from Auckland 3 November 1894. She was 27, single, nurse, English, going to San Francisco. Previously resident in Sydney, never been to USA, not going to join relatives. Arrived 22 Nov 1894. “English” merely meant her ethnic group, which turned out to only be her mother’s side, her father being born in Ireland. I then turned to the priced Ancestry genealogy database and the free California newspaper database http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc . Between them they revealed a lot — but, as always, not quite enough to satisfy my curiosity.

The 1900 US census gives her at 997 Market Street, San Francisco as a lodger. She was Judith B. Dwyer, 32, born Australia, who had arrived in the USA in 1894. Her occupation was as a medium. Both her unusual name and the occupation were very helpful, and her age matched the shipping record. Her first appearance in the San Francisco Call is on 18 Dec 1898, with a full article by “Mrs Judith B. Dwyer, spiritual reader”. The Mrs is presumably honorific, such as for couturiers. It makes several predictions: an attempt will be made on the life of President McKinley in May 1899 [he was assassinated, but in September 1901], Queen Victoria will live for 7 years [it was just over two], in 1899 Germany and the USA will be engaged in a war [true, but not until 1917]. The same newspaper had an advertisement by her in the 13 August 1899 issue, saying she graduated from the ‘highest professor in occultism.” She charged $1, with a reduction available for the poor. Best of all, there is a sensational account in the 22 October 1899 issue. http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=SFC18991022.2.111&srpos=1&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN-%22Ella+P.+Reed%22——-1

The same newspaper had an article (calling her Miss, clairvoyant and medium) about an alleged plot to murder her with a box of candy. It had been delivered anonymously to the boarding house on Market Street where she lived. Fortunately, as she and the landlady’s daughter, Ella, were about to taste it they felt warned not to. They broke it open, and saw blue chunks in it. I quote: ‘“It is bluestone [a poison]”, moaned Miss Dwyer. “Me hated rival has been spoiled by me faithful spirit.”’

Police put no credence in the story, and neither apparently did the newspaper, with the subtitle “Scenes and actors in a candy comedy”. Lurid drawings of her and Ella illustrated the top of the article. So what happened to Judith ? There, as far as I know, the trail ends.